Sometimes I cannot figure out how or why something jumps to the forefront of my mind, but other times the connections are obvious: Sonny Rollins –> The Bridge, a recording by Rollins –> The Bridge, a book by Gay Talese. What follows are just some random thoughts about a book I love; please do not construe this to be a book review.

Back in June, in a post about Describing Real People, I mentioned Gay Talese’s vivid characterizations in The Bridge (originally published by Harper & Row in 1964, re-issued in paperback by Walker & Company in 2003. Unlike most of Talese’s humongous tomes, this is a mere 147 pages; a quick and wonderful read, and it is one of the very few books that I like to re-read.

Talese has a certain symmetry and cadence to his writing style, and many of his sentences are quite long. Here’s an example of an amazingly long sentence — 138 words on pages 22:

“And that is how it went on each block, in each neighborhood, until, finally, even the most determined hold-out gave in because, when a block is almost completely destroyed, and one is all alone amid the chaos, strange and unfamiliar fears sprout up: the fear of being alone in a neighborhood that is dying; the fear of a band of young vagrants who occasionally would roam through the rubble smashing the windows or stealing doors, or picket fences, lighting fixtures, or shrubbery, or picking at broken pictures or leftover love letters; fear of the derelicts who would sleep on the shells of empty apartments or hanging halls; fear of the rats that people said would soon be crawling up from the shattered sinks or sewers because, it was explained, rats also were being dispossessed in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn.â€

There seems to be symmetry to the chapter structure too:

-

1. Intro—————————————————————————10. End

- 2. Brooklyn—————–(Brooklyn)—————————————9. Brooklyn

-

3. Designers—————(a breed of their own)———————8. Indians

-

4. Punks/Pushers——–(people & job details)———————-7. Stage

-

5. Benny———————(avoiding/experiencing death)———6. Death

Throughout the book, Talese’s style of reporting is completely devoid of opinion or pronouncement. In a discussion about disasters caused by shortcuts or inferior materials, Talese reports without even a trace of judgment in his tone. This even-handed objective voice is also what allows Talese to describe whole groups of people without seeming politically incorrect — for example, “the lace-curtain Irishâ€

When there are lots of numbers and statistics, he uses description by comparison to provide some perspective for the reader. For example, the bridge would require 188,000 tones of steel, a figure that means nothing to me. But when told that it is three times the amount used in the Empire State Building, I have some idea of the magnitude. Throughout the book there are zillions of facts and numbers, fascinating to an aficionado but way too much for a casual reader like me. What keeps me (and I suspect many others) reading, is the alternating between these lessons and the personal stories that are fraught with the tension of competition, accidents, and death. There is a tremendous amount at stake including dollars, reputations, and lives.

If you have a fascination for bridges, you’ll love the photos and appendix full of factoids, but you need not be interested in bridges to love this book.

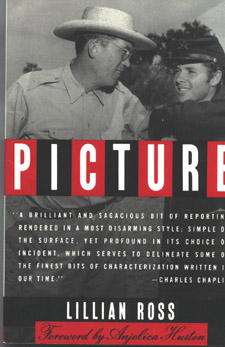

One of my goals as a narrative nonfiction writer is to make my readers to feel as if they are there, seeing the events about which I am writing. In order for that to happen, I have to evoke the readers’ interest and convey to them a sense of my reliability, letting them know that either I was there observing (and now they can watch through my eyes) or at least that I did thorough research. Lillian Ross is a master in this genre and I often try to analyze her work in search of techniques that I might employ. Her ability to capture dialogue without aid of a tape recorder is truly amazing (and something I may never be able to do as skillfully as she), but there are a few techniques I can emulate.

One of my goals as a narrative nonfiction writer is to make my readers to feel as if they are there, seeing the events about which I am writing. In order for that to happen, I have to evoke the readers’ interest and convey to them a sense of my reliability, letting them know that either I was there observing (and now they can watch through my eyes) or at least that I did thorough research. Lillian Ross is a master in this genre and I often try to analyze her work in search of techniques that I might employ. Her ability to capture dialogue without aid of a tape recorder is truly amazing (and something I may never be able to do as skillfully as she), but there are a few techniques I can emulate.