The New York Times ran a huge feature story about it last summer, it’s been tauted by a popular arts blogger (here and here and here), and the main stream press and wire services were abuzz about it after this year’s Grammy Awards. The “it” to which I refer is ArtistShare. ArtistShare is a new concept in Internet marketing and distribution, one that not only returns control to the artist, but also renders moot the fears of digital piracy. Mastermind Brian Camelio, sympathetic to the plight of his music friends, and tired of record companies bemoaning their losses, came up with the concept to empower the artists. As he explains it, “The answer is to market what cannot be pirated: the artist, the artist’s creation process, a fan’s love of an artist’s work. The fan is now part of the creation process, not the litigation process.â€

Several jazz artists have now launched ArtistShare websites, among them Maria Schneider, Jim Hall, Jane Ira Bloom, Brian Lynch , and most recently, Bob Brookmeyer, to name only a few. In this model the customary end product, such as a CD or a copy of a music score, turns out to be a by-product, while the sharing of the artistic process becomes the primary product – a product that is experienced over time as it evolves. The behind-the-scenes exposure is provided by media events such as streaming audio and video clips of rehearsals and meetings, photo galleries showing the artist at work, perhaps a pdf peak at the first draft of a new score or an audio lecture analyzing a composition, and journal entries about the project’s progress. Another perk at certain levels is the participant acknowledgement – for example, the placement of the participant’s name in booklet accompanying a new CD.

Because participation in the process is now the product, what might have been viewed as pre-sales now becomes the source of funding for a project. By offering varying levels of participation, an artist can target specific groups of fans. For example, Jim Hall offers guitar lessons posted online for Player Participants, and both Maria Schneider and Bob Brookmeyer offer lessons and scores for Composer Participants. Whether you are an average listener, fellow composer or musician, an aspiring executive producer, or a jazz philanthropist, there is a particiation level for you. If you’re a true jazz fan and arts lover, you’ve got to check it out!

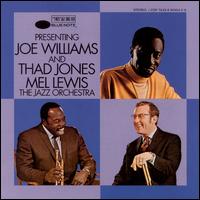

My favorite male singer has always been Joe Williams. I never got to hear him sing live with the Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra, but one of my favorite recordings from the days of yore was an early morning session they did with Joe in 1966. When I say early morning, I don’t mean the wee small hours — which might have been preferable as the band had been playing the night before until one or two o’clock in the morning. With a recording session just a few hours off, most of them didn’t bother to go home. They just hung out, had few drinks, ate some breakfast and showed up at the studio ready to play some more.

My favorite male singer has always been Joe Williams. I never got to hear him sing live with the Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra, but one of my favorite recordings from the days of yore was an early morning session they did with Joe in 1966. When I say early morning, I don’t mean the wee small hours — which might have been preferable as the band had been playing the night before until one or two o’clock in the morning. With a recording session just a few hours off, most of them didn’t bother to go home. They just hung out, had few drinks, ate some breakfast and showed up at the studio ready to play some more.  Have you ever heard of Nedra Wheeler? I can’t believe that I have not been aware of her until now, especially when I read her credits that include live and recorded performances with Ella Fitzgerald, Billy Higgins, Harper Brothers, Cedar Walton, Branford Marsalis, Billy Childs, and Stevie Wonder, to name just a few.

Have you ever heard of Nedra Wheeler? I can’t believe that I have not been aware of her until now, especially when I read her credits that include live and recorded performances with Ella Fitzgerald, Billy Higgins, Harper Brothers, Cedar Walton, Branford Marsalis, Billy Childs, and Stevie Wonder, to name just a few. after Cannonball’s untimely death. In the words of Nat Adderley, “Cannon considered Big Man one of the most important projects of his whole career. Since he had a pretty big career, you can get some idea of what it meant to him to compose the score for a full-scale musical play, and particularly this musical, dealing with a theme that has major significance for all Americans and particularly for all black Americans.”

after Cannonball’s untimely death. In the words of Nat Adderley, “Cannon considered Big Man one of the most important projects of his whole career. Since he had a pretty big career, you can get some idea of what it meant to him to compose the score for a full-scale musical play, and particularly this musical, dealing with a theme that has major significance for all Americans and particularly for all black Americans.”