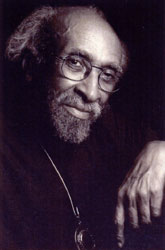

Luther Henderson is not a household name, not even a B-list celebrity in the eyes of the general public. Finding a publisher for his biography has been a lengthy and difficult process, but I am pleased to say that I have been offered a contract, am in negotiations right now, and hope to announce the signing very soon. Meanwhile, people are asking me “Luther who?” and “Why him?”

I was unaware of Luther’s accomplishments when I first met him. I do not remember how that first meeting came to be. He was close to many people who are, or were, important in my own life. Still, I don’t recall any one of them making the introduction. My earliest recollection is of a planning meeting in the mid-1970s for the annual Jackie Robinson fundraiser, “An Afternoon of Jazz,” held outdoors on the grounds of Robinson’s home in Connecticut. Someone had recommended me to assist jazz pianist Dr. Billy Taylor with booking the artists, and I was in Marion Logan’s living room with Rachael Robinson, Luther Henderson, Billie Allen, and a few others. I may have grown up as a liberal, supported Rev. Martin Luther King’s work, and taken part in the March on Washington, but back then, I was unaware that Mrs. Logan was married to Arthur Logan, Duke Ellington’s doctor, and that they were close to Martin Luther King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. I knew that Mrs. Robinson’s husband was a famous baseball player, but I did not know that it was he who broke the league’s color barrier. (Not being a sports fan, and not yet born when it happened, I guess that was understandable, but they really should have taught us about it in school.) There was no reason for me to know that Ms. Allen was an actress and stage director, or that Mr. Henderson had graduated from Julliard in 1942, but had he been properly credited on recordings, being a jazz fan, I might have known that he had written orchestrations for Duke Ellington. They didn’t seem to mind my ignorance; I was just a college kid there to do a job.

Over the following years, I would return on several occasions to the annual summer concert at the Robinsons’, no longer as naive booker, but as guest. One year I went with saxophonist Jerome Richardson, who I was dating at the time. Jerome and Luther were great friends, and Luther hired Jerome to work on his projects whenever possible. While living in New York City, I got to know Luther’s third wife, Margo, and we would occasionally shop together or have lunch at Cafe Des Artistes. I soon moved to California with Jerome, and we saw Luther on many occasions, most often during the productions of Ain’t Misbehavin’ in California and France when Jerome was in the band. After a lengthy run close to our home in Los Angeles, the show ran for six months in Paris, where I joined Jerome for a month that included Christmas and New Year’s Eve. Margo had died two years earlier, and Billie Allen flew to Paris to spend the holidays with Luther; just after New Year they announced their plans to marry.

By the time they married, Jerome and I had split up. The new man in my life was John Levy, later to become my husband. John’s client, jazz singer Joe Williams, introduced us, and both Joe and John were old and dear friends of Luther’s. I was to return again several times to the Robinsons’ with John and with Joe (by then I was Joe’s publicist), and there, while the crowd enjoyed the music outside, we would always steal a moment in the gracious Robinson living room to catch up on the latest Henderson news.

Distance makes it difficult to stay connected, and we lived on opposite coasts, but whenever John or I went to New York, or whenever Luther or Billie would come to Los Angeles, we would get together. I had been in New York to see Black and Blue when it opened on Broadway, and John and I both saw Jelly’s Last Jam, first in Los Angeles and later in New York. We knew that Luther was ill; we knew that he had cancer, but we thought he had beaten it. We would hear that Luther was very sick, and then we would talk to him and he’d tell us about a new project he was working on. This happened more than once. When the end finally came, we were blindsided, and unable to get to New York in time to see him. At least John was able to say a few words to him on the telephone during that last week when he was in hospice.

Later we learned that just a few weeks before Luther went into hospice care, Billie told him that he was to receive a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master Fellowship, an honor that pleased him greatly. She said that he responded with just one word: “Recognition.” He had little energy to say more, and died not long thereafter. John and I were not able to attend the New York memorial service, but we were there in 2004 when Billie Allen Henderson, accompanied onstage by Luther’s son, Luther Henderson III, and his daughter, Melanie Henderson, accepted the NEA Jazz Master Award in his memory.

As I watched the video montage of Luther’s life, I realized not only how little I really knew about this man and his legacy, but also how few of the three thousand people sitting around me in the immense ballroom of the Hilton hotel had even heard of him. I knew it was a situation I wanted to change.

Luther Henderson was a composer, arranger, conductor, musical director, orchestrator, and pianist. He was a proud black man who graduated from the Julliard School of Music in 1942, and in 1956, married a white woman, his second wife. He was Duke Ellington’s “classical arm,†orchestrating music for Beggar’s Holiday, Three Black Kings, and other symphonic works. Duke spoke highly of Luther, but seldom gave him the credit he was due. Luther was Lena Horne’s pianist and musical director. During his sixty-year career in music, he worked his magic on some of Broadway’s greatest musical hits, including Flower Drum Song, Funny Girl, No No Nanette, Purlie, Ain’t Misbehavin’, and Jelly’s Last Jam, starring such performers as Barbra Streisand, Laine Kazan, Robert Guillaume, Savion Glover, Andre Deshields, Tonya Pinkins, and Gregory Hines. His music was heard on television programs such as The Ed Sullivan Show, The Bell Telephone Hour, and specials for the pop stars of the day including Dean Martin, Carol Burnett, Andy Williams, Victor Borge, and Polly Bergen.

Luther Henderson was a composer, arranger, conductor, musical director, orchestrator, and pianist. He was a proud black man who graduated from the Julliard School of Music in 1942, and in 1956, married a white woman, his second wife. He was Duke Ellington’s “classical arm,†orchestrating music for Beggar’s Holiday, Three Black Kings, and other symphonic works. Duke spoke highly of Luther, but seldom gave him the credit he was due. Luther was Lena Horne’s pianist and musical director. During his sixty-year career in music, he worked his magic on some of Broadway’s greatest musical hits, including Flower Drum Song, Funny Girl, No No Nanette, Purlie, Ain’t Misbehavin’, and Jelly’s Last Jam, starring such performers as Barbra Streisand, Laine Kazan, Robert Guillaume, Savion Glover, Andre Deshields, Tonya Pinkins, and Gregory Hines. His music was heard on television programs such as The Ed Sullivan Show, The Bell Telephone Hour, and specials for the pop stars of the day including Dean Martin, Carol Burnett, Andy Williams, Victor Borge, and Polly Bergen.